Nonfiction and fiction are two huge categories in the book world, and rarely do they cross over, however, memoir is a category that bridges the gap. Memoir writers often take cues from fiction and incorporate them into their work. In Jessica Page Morrell’s book, Thanks, But This Isn’t for Us, she states, “Readers read memoirs to observe the shape of a life, uncover themes and meaning, and find directions in their own lives. The best memoirs transform our memories into what life means.” (pg. 253)

You might think this only applies to memoir writing, but elements of it—along with techniques used by fiction writers—can enhance any form of writing. I believe that nonfiction as a genre can learn a lot from fiction. Here are some tools to help elevate your nonfiction book—whether it’s a memoir, manual, academic research, or anything in between.

Reading is Research: Learning from Writers

The best way to help improve your nonfiction writing—besides writing—is reading. When you read another’s work, you are subconsciously analyzing how they structured their story, the language they use, and their voice. You’ll see what they are successful at and what they aren’t. You’ll find elements that you want to implement in your own work. In Stephen King’s book, On Writing, he says, “If you don’t have time to read, you don’t have the time (or the tools) to write. Simple as that.” (pg. 147)

Pacing & Flow: Applying Fiction’s Structure to Nonfiction

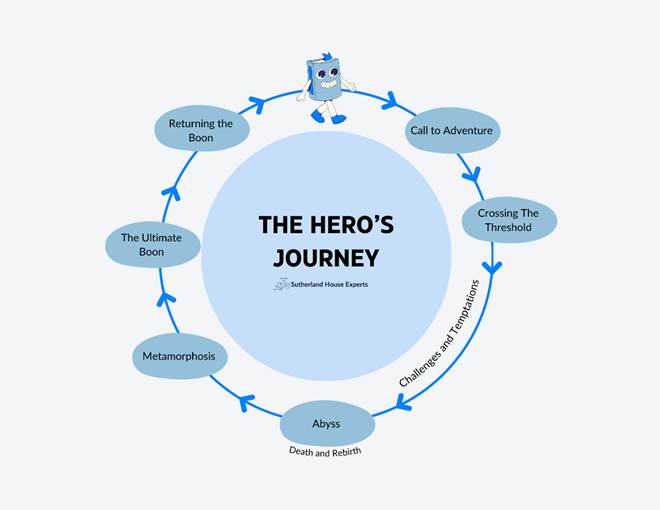

Fiction writers often use structured story arcs. Think of a three-act structure, that is often used in plays or scripts. Think of Blake Snyder’s Beat Sheet from Save The Cat! The Last Book on Screenwriting That You’ll Ever Need (pg. 70). Think of the Heroes Journey, also known as the monomyth, which is a classic template used for story structure.

Click here to learn about the Hero’s Journey more in-depth

While these structures are mostly used for narrative, there are lessons here that can be applied to nonfiction; they are there to help plan out your story. For example, think about your nonfiction book as a journey. What are the beats you want to hit in your book, and when? What are the messages, themes, and lessons you want to impart in your manuscript? In Jessica’s book, she says, “If you don’t know why you’re writing in scenes or creating plot points, you’ll muddle along and end up with a lot of words, but those words won’t add up to a story.” (pg. 35) By applying these techniques, you can elevate your nonfiction writing and ensure it has a clear and engaging narrative flow. You don’t have to have everything planned out, but make sure you know where you are going.

Repetition: Avoiding Stale Language

In fiction writing, repetition is a tool used sparingly, but when done correctly, it can create rhythm and reinforce themes. Unless your repetition is intentional, make sure to vary your text/verbiage/sentence structure so that your words don’t sound stale. A reader doesn’t want to feel like they are rereading something that they have already read. When you are rereading your manuscript, take notice of what sticks out to you. Do you see any words you tend to gravitate to? Have you written about the same topic again but in a different way? Make sure if you are revisiting a thought, you have something new to say.

In the same breath, don’t change your language so far that it’s not your voice anymore. In Stephen’s book, he says, “Put your vocabulary on the top shelf of your toolbox, and don’t make any conscious effort to improve it… One of the really bad things you can do to our writing is to dress up the vocabulary, looking for long words because you’re maybe a little bit ashamed of your short ones. This is like dressing up a household pet in evening clothes.” (pg. 117) A reader can sense when you’re being inauthentic, so there’s no need to try to impress them. They are reading your book to connect with the real you.

Dialogue: Bringing Nonfiction to Life

Nonfiction may not always include dialogue—such as if you are writing a textbook or an academic journal—and may not be relevant for you. However, for those incorporating dialogue into their book, this is important to know: dialogue needs to sound natural in order for it to work. It’s not the same as academic writing or prose. When speaking, vernacular and grammar often change, and we typically don’t follow proper sentence structure. Speak your dialogue out loud and listen to how it sounds. Does it sound natural? Is this how you speak, or how your “character” speaks? In Jessica’s book, she says, “Dialogue is never a copy of real-life speech—it’s more like conversation’s greatest hits…Good dialogue is spontaneous and natural but leaves out the boring parts of life and is often a power struggle or power exchange. We use dialogue because it shows instead of tells.” (166)

Show, Not Tell: Fiction’s Key to Engaging Readers

One of the best-known lessons in fiction writing is “show, not tell,” which can be just as powerful for nonfiction. If you find yourself explaining an event that happened, why not show it? Readers don’t want to be told how to feel; it’s more fulfilling and impactful for them to discover it for themselves. In nonfiction, this can mean using real-life examples, vivid details, and personal anecdotes to illustrate your points, rather than simply stating facts or conclusions. This is particularly important, as it transforms abstract concepts or statistics into relatable and human stories, making your message resonate with your audience. Stephen states, “What you need to remember is that there’s a difference between lecturing about what you know and using it to enrich the story. The latter is good. The former is not.” (pg. 161) By showing the reality of a situation—whether it’s a personal struggle, a breakthrough, or a lesson learned—you invite the reader to experience the narrative more deeply.

Trust Your Reader: Subtlety Goes a Long Way

The reader is smart – smarter than you think. There’s no need to spell out every detail or repeat ideas they’ve already grasped. Readers appreciate subtlety, whether it’s in foreshadowing, thematic hints, or emotional cues. When foreshadowing, it must be woven seamlessly into the story—too subtle, and it loses its impact; too heavy-handed, and it risks making the reader feel like they are being spoon-fed information. Allow the reader space to draw conclusions, to wonder, and to piece things together. Overexplaining not only slows the pacing of your book but can also disengage your audience.

Conclusion: Elevate Your Nonfiction with Fiction Techniques

The key to writing compelling nonfiction lies in blending storytelling with solid research and facts. By using techniques such as structured pacing, vivid dialogue, and the principle of showing rather than telling—you can enhance your writing and keep your readers engaged from start to finish.

A lot of these issues you may be facing will be more apparent after you reread your manuscript. The first draft is to just get the words out. The second, third, or however many other times you reread, is when you revisit these areas of focus, and when your book will become more polished and ready for publishing. At Sutherland House Experts, we are here to help elevate your book from that of a novice writer to one of an experienced expert.

Books you should read to improve your writing:

- On Writing by Stephen King

- Thanks, But This Isn’t’ For Us by Jessica Page Morrell

- Save the Cat! by Blake Snyder (there are multiple editions of this book, I suggest reading Writes a Novel or The Last Book on Screenwriting That You’ll Ever Need)

What fiction techniques have you found helpful in your nonfiction writing? Email us your thoughts!